JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA—After a week of ministry in Australia and New Zealand, Deborah and I flew across the Indian Ocean to Johannesburg, South Africa, to preach at our Every Nation Word and Spirit Conference.

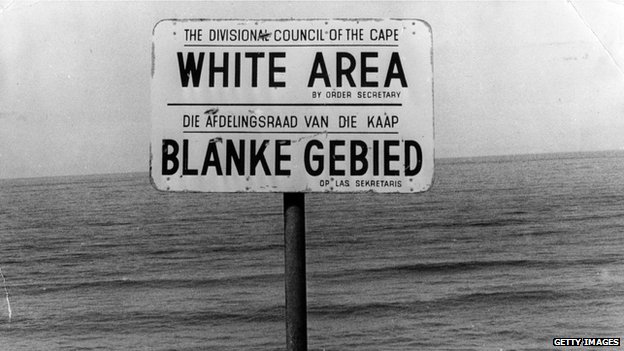

Before our meetings started, we visited the Apartheid Museum, a moving and powerful reminder of the ugliness of racism and the beauty of reconciliation. It was a humbling reminder that Christians in every age have blind spots that can only be identified and fixed when we intentionally walk in multiethnic and multigenerational Christian community.

Like the Jim Crow era segregation in the American South, Apartheid in South Africa was propagated, supported, and defended by Christians. Often our knee-jerk reaction to these painful realities of church history is to assume that the “Christian” defenders of Apartheid or Jim Crow were not real Christians. Maybe they were just cultural Christians, or maybe they were theologically liberal Christians who didn’t actually believe the Bible.

Unfortunately, history won’t let us off the hook that easily.

I am sure that some defenders of segregation in both South Africa and America were only nominal Christians and others may have been a part of churches that stopped believing the Bible. But many defenders of segregation on both sides of the Atlantic were members of churches that we might have attended had we been around in those days. To put it bluntly, many of them were Bible-believing Christians.

Not only did they defend racial segregation on national and cultural grounds, but they also defended it on biblical and theological grounds. They were wrong. They were sinning. And they didn’t see it.

It was a blind spot.

There were certainly many white South African Christians under Apartheid who were kind and loving to people of other races and did not personally discriminate against those from whom they were legally segregated. And yet, many of those same people saw nothing wrong with the Apartheid system they were living under. It was a blind spot.

The same could be said for my upbringing in Mississippi. I grew up in a white neighborhood, played golf at a white country club, played baseball on a white Little League team, and attended a private white prep school. In my world, segregation was normal, until I got involved in a multiethnic campus ministry and traded my white world for a world with color. As I developed friendships with people who did not look like me, I could see in their faces the pain of discrimination and the folly of segregation.

The sinful tendency to segregate on racial, ethnic, and cultural lines is not new.

In the first-century church, Jewish disciples often excluded Gentile believers from fellowship because they held to a cultural notion that Gentiles were unclean. This meant, among other things, that many Jewish believers refused to eat with Gentile believers. And this was not just a practice of a fringe group of Jewish legalists in the early church.

Peter and others among the original twelve participated in the segregation of Jewish and Gentile believers. For Peter to repent and change, he needed a powerful encounter with God, an unlikely friendship with a Roman soldier named Cornelius (see Acts 10–11), and a very public rebuke from Paul (see Galatians 2:11–16).

In every time and place, the local church has blind spots—areas of both personal and public sin that to them look less like sin and more like the status quo, that looks less like oppression and more like law and order. Things that should break our hearts but don’t even catch our eye. Things that should be shocking but seem mundane. Things that will make future generations of Christians wonder: How could they call themselves Christians and not see that?

This sobering reminder from church history should remind us that planting multiethnic and multigenerational churches is not just an option for the ambitious church planter. Diversity is not an option. It’s a necessity. If we only build with people who look just like us, we will exclude the very people whom God has ordained to help us see our blind spots.

In the words of C.H. Mason, a Pentecostal saint of old: “The church is like the eye. It has a little black in it and a little white in it, and without both, we cannot see.”